Route Shopping: The Matterhorn

Iconic peaks seem to stir something within our souls. They stand in resolute isolation, their towering heights and sheer faces impervious from the valley floor. They exude power, majesty and enslave any alpinist who dare stare too long, tracing its ridges and routes to the summit.

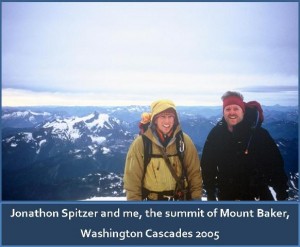

I must confess the Matterhorn has cast its spell on me. This summer I, along with friend and guide Jonathon Spitzer, plan to stand atop the Matterhorn’s 14,492-foot summit. I first met Jonathon in 2005 when he was an instructor for the American Alpine Institute’s 19-day Alpine Mountaineering and Technical Leadership course. We really hit if off. He was a great instructor, and together, we did my very first technical climbs. July 2013 we’ll spend a week in Zermatt, Switzerland and climb 2-3 other peaks before we attempt our main objective, and what an objective it is.

Cervino to the Italians, Mont Cervin to the French, and Matterhorn to the rest of the world, this perfect pyramid of rock and ice was the last great Alpine peak to be climbed. It was Edward Whymper, a young Englishman entranced by its impressive ridges, who stood triumphantly on its snowy summit for the very first time on July 14, 1865. After celebrating their astonishing achievement, Whymper and his 6 other companions roped up and began their descent. In an instant, their triumph turned to tragedy as Hadow, the least experienced of the group, slipped on the steepest section dragging the whole party down the mountain. Suddenly the rope broke. Hadow and three other climbers careened down the north face to their deaths. Shocked and despaired, Whymper and the Taugwalders made it down to safety and into a media firestorm. Queen Victoria was so appalled at the tragedy that she considered banning climbing altogether.

Jonathan and I will be trudging in the same steps of that first assent, but hopefully with a less dicey descent. There are numerous hazards on this mountain; climbers need to be good at route finding, acclimatized for the altitude, able to move unroped on easier sections, avoid its notorious rockfall, and climb mixed terrain in crampons both up and down the mountain. The Matterhorn is considered one of the deadliest mountains in the world having claimed more than 600 lives. Climber David Defranza lists it as number 6 in his top 11. Check out his list to see which mountains you may want to take off your list.

Once you have chosen a mountain to climb, the next task is to select the route you will take to the summit. Oftentimes people think there are only a handful of ways to ascend a peak, but actually most mountains have many routes to choose from. Selecting a route involves a lot of research studying guidebooks, trip reports, pictures, and topo maps until you pick that perfect route – an exercise I like to call route shopping.

There are many factors to consider. First off, selecting routes that are within your skill level. Each climber has their own unique set of skills; some may be great rock climbers, but uncomfortable with an ice ax and crampons, comfortable on a sheer face, but not routefinding on an exposed wandering ridge on a big, remote mountain. While climbers do want to challenge themselves, they also have a sense of how much inherent danger is too much.

All major routes are rated with systems that describe the overall difficulty of the route, the overall seriousness, commitment, hazards, remoteness and the difficulty of retreat in case of bad weather. They also rate the most difficult rock moves, overall technical difficulty of a route, steepness of ice and snow, and the time required for a competent party to complete the route.

While all this is very helpful, it is made even more challenging by the different rating systems used throughout the world. Ratings are somewhat subjective. For instance, the rock climbing grades in the U.S. use the Yosemite Decimal System, but I can tell you a 5.9 in the Eastern Sierras is not always the same as a 5.9 in North Carolina – although I can fall off anything 5.10 and above regardless of location! The French Alpine Rating System combines the seriousness of the climb and the overall difficulty into two rankings. I feel it does the best in describing Alpine climbs, but I’m sure the Kiwis would scoff, preferring their own New Zealand Alpine Rating System.

So it’s not an exact science by any stretch. There are some lists that show classic climbs and how each system ranks them. Once you have climbed a number of these classics, the mystery of ratings begins to reveal itself. This has helped me immensely as I know what is within my capabilities and what is not, what will stretch me and what will just be a nice easy acclimatization climb on day one. A much better way that counting the times you scream for your mother on a IV/TD (very difficult) when you should have been lazily enjoying a II/F (easy).

In addition to the overall difficulty and skills required, there are a myriad of other factors to consider, difficulty and length of the approach, are there huts or will you need a camping or bivouac permit, how many days will the climb take, what equipment will be needed, and once you’re off the mountain where is the closest beer and a shower.

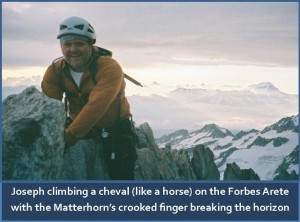

Route shopping the Matterhorn was a joy with over 28 routes and variations on a near perfect pyramid with four stunning ridges and four faces to keep the interest of Alpinists of every level. Running from NE to SW is the Hörnli ridge in Switzerland and the Lion ridge in Italy, the first two ridges to be climbed. The Zmutt ridge in the NW rises and falls to the Furggen ridge in the SE, the last ridge to be climbed in 1880. As with most mountains, once the easiest routes have been conquered people begin to seek new and more challenging ways to the summit. The South and North faces have the most routes, and many of the most difficult including the Bonatti route, which its namesake Walter Bonatti soloed in winter on the 100th anniversary of the first ascent.

Do your own route shopping with this flyby of the iconic Matterhorn

This video begins by flying up to the North face with the Zmutt ridge on the right and the Hörnli ridge on the left side, then around to the East face with the Hörnli ridge on the right and the Furggen ridge on the left skyline. Then continues on to the South face, past the Furggen ridge and West face and the Zmutt ridge before ending with a close up of the Hörnli ridge.

After studying routes, ridges, and variations, the Hörnli ridge is the one for Jonathon and me. It is one of the most historic in the Alps, with one of the most aesthetic views in the range, and the longest of the ridge climbs with over 4,000 vertical feet between the hut and the summit. That’s fine by me. I always prefer more mountain – not less.